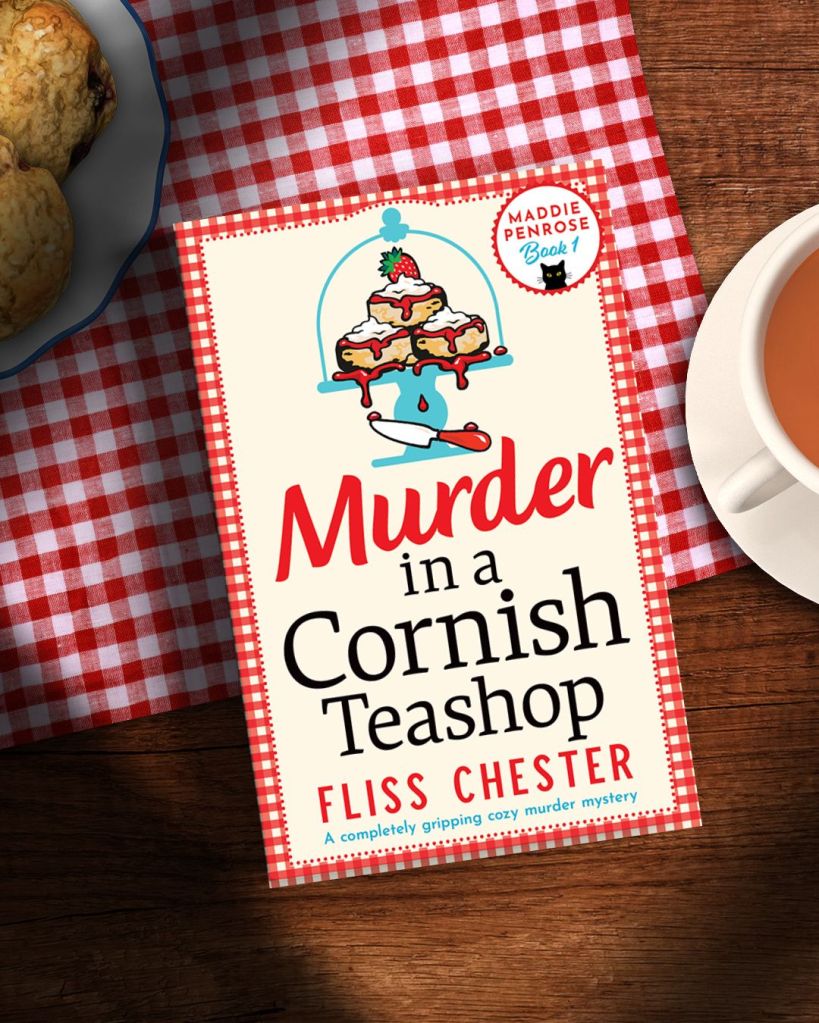

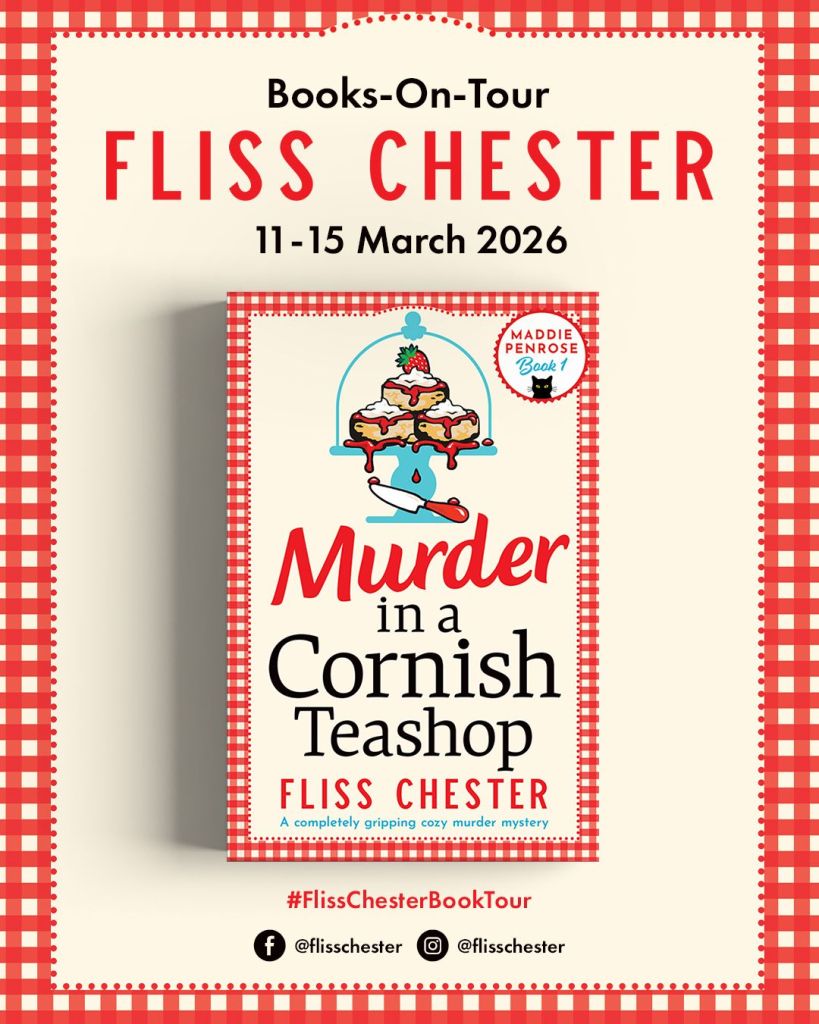

A Cornish clifftop, a sunny afternoon, a quaint little teashop… but wait a minute. Is that jam, or blood? Maddie Penrose is determined to find out!

Maddie Penrose is staying with her beloved grandmother, Nor, at her gorgeously idyllic Cornish farm. She’s looking forward to days helping out in Nor’s little teashop and evenings wandering down the cliff path to watch the sunset. But before Maddie has even finished serving up scones on her first morning, a man bursts through the door: Nor’s neighbour Clive has found a body in the field behind the teashop…

Maddie is straight to the scene, fancying herself as a bit of an Agatha Christie. But solving this mystery is far from a piece of cake. Her list of suspects is jam-packed with locals, with some a little too close to home: the newcomer renting out one of Nor’s barns is acting suspiciously, the victim’s boyfriend has disappeared without trace, and Clive isn’t really Maddie’s cup of tea either…

But the proof is in the pudding when there’s another murder – her prime suspect is dead. And when Maddie finds a backpack belonging to the first murder victim, her diligent notetaking and quick thinking leads her to discover that the killer will act again, and soon. Maddie is horrified to discover that it looks like she is their next target…

Can Maddie and Nor work as a team to piece together the puzzle? Or will murdering Maddie be the icing on the cake for the killer?

A totally addictive, witty and warm cozy mystery that will keep you reading late into the night, perfect for fans of Agatha Christie, T.E. Kinsey and Verity Bright.

Fliss Chester lives in Surrey with her husband and writes historical cozy crime. When she is not killing people off in her 1940s whodunnits, she helps her husband, who is a wine merchant, run their business. Never far from a decent glass of something, Fliss also loves cooking (and writing up her favourite recipes on her blog), enjoying the beautiful Surrey and West Sussex countryside and having a good natter.

Mailing List Website Instagram Facebook

My thoughts: I really enjoyed this mystery set in my beloved Cornwall and investigated by someone who has a very similar name to mine!

Maddie is staying with her nan, Nor, who runs a tea shop on the family farm, and as a chef, she’s helping out with the baking. When the neighbouring farmer appears in the cafe covered in blood, she knows exactly what to do, call 999 and put the kettle on.

Maddie’s intrigued by the murder, and starts doing a bit of investigating of her own, plus the police detective in charge is rather dishy.

The case has plenty of twists and turns, and Maddie is learning a lot about the village and its residents. She’s writing a rather unusual recipe too – one that might end up in solving a murder. With help from two of the best named cats around – Crumpet and Toast.

I loved Fliss Chester’s other books and this was very good, and I’m looking forward to seeing what Maddie and Nor cook up next.

*I was kindly gifted a copy of this book in exchange for taking part in this blog tour, but all opinions remain my own.